Villers-Bretonneux

Operation Michael

21 March 1918

At the end of 1917 the German High Command made the decision that they would have to make an all or nothing gamble in the spring of 1918. For a fleeting moment German resources unlocked from the Eastern Front, following the collapse of Russia, would offer numerical supremacy on the Western Front. With the reality, however, of fresh young American soldiers arriving by the boat load, Germany could not wait too long before the numbers began to turn against them — and the Americans were not yet war weary, they were ready for anything.

On a foggy 21st March, General Ludendorff launched Operation Michael against General Sir Hubert Gough’s Fifth Army in the area around St Quentin. Gough may not have been brilliant but this was one scenario where he had little control over events. His men were required to hold a line that was too long with too few soldiers and few prepared positions.

Fifth Army was all but brushed aside and Gough was removed. The Germans made enormous gains, capturing much of the old Somme battlefield of 1916 within days — ground that had taken the Allies months of painful progression to acquire.

In 1917 the Germans retired across wide sectors to their newly created Hindenburg Line (as it was known to the Allies). In the course of that retirement they operated a scorched earth policy. They even named it Operation Alberich after the evil dwarf from the Nibelung Saga.

The Germans had progressed but at the cost of great losses in highly trained storm troopers and were now in possession of ground they, themselves, had wrecked. The steam roller, ran out of steam.

Ludendorff now turned his attention towards Flanders for his second offensive of the year — launched on 9th April.

Before that, though, he wanted to have another crack at taking Amiens, an important logistics base for the British and French.

The area of front defending Amiens also marked the junction between the French 1re Armée and the British Fifth Army. Each with its own strategic requirements. The French would guard Paris, the British the Channel ports.

Without an overall command structure the Allies risked splitting down the middle. For that reason a hastily convened meeting at Doullens on 26 March 1918 conferred on Général Ferdinand Foch command over both British and French forces on the Western Front.

Général Foch explains how Amiens must be held

4 April 1918

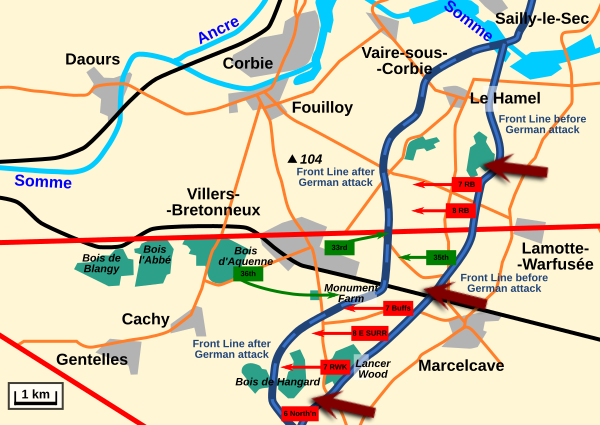

By 4th April the Germans held a front which ran at a slight SW-NE oblique in front of Villers-Bretonneux. On the British side Gough had been replaced by General Sir Henry Rawlinson and his Army renamed and reorganised as the Fourth Army (which Rawlinson had commanded during the Somme campaign of 1916).

A Defence Line was drawn up in front of Amiens ; centred on Villers-Bretonneux, the last major town on the main east-west axis before Amiens. The line was held by a mix of British and Australian battalions forming the British 18th and 14th Divisions. To the south the French covered the line from Hangard.

At 0630 hours on 4th April, following an hour of heavy bombardment, the German infantry launched their assault. Against the French, gains were made in the area around Moreuil (south of Hangard) and a dangerous dent was created in the line before reinforcements could bolster it.

Directly in front of Villers-Bretonneux, between the main road and the railway line, was the 35th Australian Battalion (From their 9th Brigade — attached to the British 18th Division). Steadfast throughout the morning they stood their ground, repulsing three determined assaults by the 9th Bavarian Reserve Division.

On their left , however, the British 41st Brigade (14th Division) fell back from in front of Le Hamel to the area now occupied by the Australian Memorial (Hill 104). Then the Australians realised that the 7th Bn Buffs on the other side of the railway line had fallen back into Villers-Bretonneux. On the far right of the British line, Lancer Wood and most of Hangard Wood were lost.

At 1715 hours the 36th Bn AIF launched a counter-attack ; with the aid of their 35th Bn they managed to eject the Germans from Monument Farm and, by the following morning the support line had been secured.

They had been ably assisted by five Canadian motor machine-gun batteries.

For the moment the German advance on Amiens had been halted. Operation Michael came to a close and a few days later the Germans launched their next assault — against the Portuguese in Flanders.

There was now a clear salient around Villers-Bretonneux along the railway line.