Saint Omer Aerodrome

Introduction

Isn’t it amazing how in the modern world we take air power as a prerequisite for winning our wars.

How far we have come from wood, wire and fabric at Kittyhawk in 1903 to modern aircraft capable of flying faster than sound.

Even as civilians, most of us think nothing of hopping on a plane to go on holiday, yet in 1909 when Louis Blériot made his flight across the English Channel this was considered an outstanding achievement for him and aeroplane — ironically many of us now go under the channel rather than over it!

The Air Services Memorial at Saint Omer

The French took up the idea of aviation very quickly and by 1911 had about 200 aircraft as opposed to the less than 20 in the British Army.

It had been French engineers who had invented the rotary engine which prevented the engine from over heating and allowed greater stability in flight. This of course was still the age of the horse and the French had almost more aircraft than they did lorries !

Famously, Général (Later Maréchal) Ferdinand Foch remarked that aeroplanes were fine for sport but he failed to see what further use they might serve.

On 13th April 1912 the British formed the Royal Flying Corps, recruiting initially from within the Army and in particular the Royal Engineers. At the turn of the century, Britain’s Royal Navy truly ruled the seas and the Admiralty had so much power that it not only ignored the fledgling RFC but formed its own air force: The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS).

Joining the British Expeditionary Force

At the outbreak of war in August 1914 the RFC had four squadrons equipped with aircraft: No’s 2, 3, 4, and 5 Squadrons. No 1 Squadron had been formed as an airship unit and had yet to be re-equipped.

On 13th August 1914 Nos 2, 3, and 4 Squadrons took off from Dover to join the BEF in France, No 5 Squadron following a few days behind.

914 (Glastonbury & Street) Squadron ATC, June 2011

The flight was considered an enormous and dangerous adventure and took them directly across to Boulogne and then down the coast to the Bay of the Somme before following the river to Amiens, a journey of some 2 hours for the fastest.

Moving forward to Maubeuge (near the Belgian border) with the Army the RFC completed its first Reconnaissance Flights on 19th August, and shortly afterwards the RFC found itself in the midst of the Battle of Mons on 23rd August 1914.

914 (Glastonbury & Street) Squadron ATC

Flying at this moment in time was obviously in its infancy and the pilots and observers simply provided an eye in the sky for the fighting men below. The benefits though were soon realised, and were used, not just to seek out the enemy, but also to assist in locating friendly forces as well.

Following the retreat from Mons the RFC fell back to the Marne where in September they helped in identifying von Kluck’s 1st Army’s left wheel against the exposed French flank. In making his manoeuvre in front of Paris von Kluck gave the French a chance to counter attack, turning the tide in favour of the Allies.

The German manoeuvre exposed their own flank to the Paris garrison – the incident of the Taxis of the Marne.

In the battle of the Aisne which followed, as the Germans were pushed northwards, the RFC took aerial photographs for the first time and made use of wireless telegraphy to guide artillery.

A new base for the RFC

As the Race to the Sea developed the RFC moved forward again and on 11th September 1914 the first RFC aeroplane touched ground at the aerodrome of Saint Omer.

Then on 8th October 1914 the Headquarters Royal Flying Corps arrived and took up residence at the aerodrome which just so happened to be next to the local racecourse.

The location (in the commune of Longuenesse) may well have been fitting as a number of flying instructors considered that cavalrymen had a better feel for the ride of their machines.

Within a few days the four squadrons had arrived and for the next four years Saint Omer was to be a central hub for the RFC.

Most squadrons only used Saint Omer as a transit camp whilst on their way to other locations, but the importance of the site grew as logistical support became its primary function.

The GOC RFC; Major General Hugh Trenchard held his headquarters here up until the end of March 1916 and it returned again for a few months in 1917.

The Pilots’ Pool was to remain at Saint Omer until the closing stages of the war, and so from this aspect Saint Omer became well known to every pilot in the service.

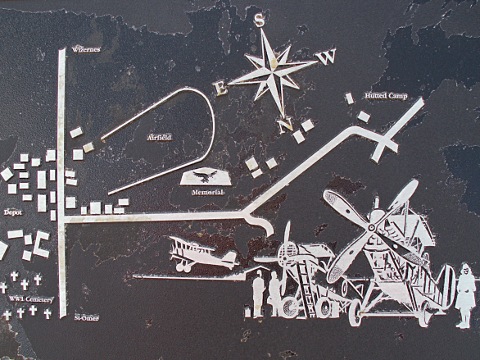

Detail on the plaque showing the location of the buildings

At the beginning of the war some senior officers had professed doubts as to the purpose or requirement to having men flying about above the lines. This changed rapidly as pilots turned from being mere observers to active participants. Revolvers were taken aloft as personal protection and became offensive when pilots started taking pot-shots at each other.

From there on in it was only a matter of time before machine guns and bomb dropping equipment had been added to machines.

The French Ace Roland Garros initially solved the problem of forward fire by armouring his propeller blades and became the first person to down another aircraft by firing through the propellers on 1st April 1915.

Garros was brought down on 18th April 1915 and taken into captivity. His Morane-Saulnier Type L was examined by Dutchman Anthony Fokker (Who had offered to work for the Allies but been turned down). Fokker developed the concept with the invention of a synchronisation system that would change air combat.

Garros was an avid tennis player and the stadium he attended whilst studying in Paris is now named after him. It is the French equivalent of Wimbledon.

Such changes necessitated an increasing number of aircraft and pilots. Equipment had to be repaired and machines put back together again. Wireless equipment was eventually added and Saint Omer was at the forefront of this huge behind-the-scenes operation.

Hugh Dowding forms IX Squadron

One of the duties of the RFC was to assist the artillery with ranging onto targets. Many systems were tried, but klaxons couldn’t be heard, semaphore was next to impossible and the only thing that looked promising was the wireless. To this end the Wireless Flight of 4 Squadron was increased and reformed at Saint Omer as IX Squadron RFC.

The commanding officer of IX Squadron was Captain Hugh Dowding who would later find himself at odds with Trenchard over the necessity of giving pilots adequate rest periods. For his stance Dowding was sent back to Britain. However as Air Marshal Dowding during the Second World War he was to find himself in Trenchard’s shoes commanding The Few during the Battle of Britain when his own pilots were to fight to their very limits.

During the 2nd World War the aerodrome would become the base of Adolf Galland’s Jagdgeschwader 26.

When the RAF Ace Douglas Bader was forced to bail out over Saint Omer on 9th August 1941 (having to leave his right tin-leg in the cockpit) he was invited to the base by Galland who treated him with great courtesy and arranged for the RAF to drop a replacement limb by parachute over the aerodrome.