Hill 70

The Green Crassier

23rd August 1917

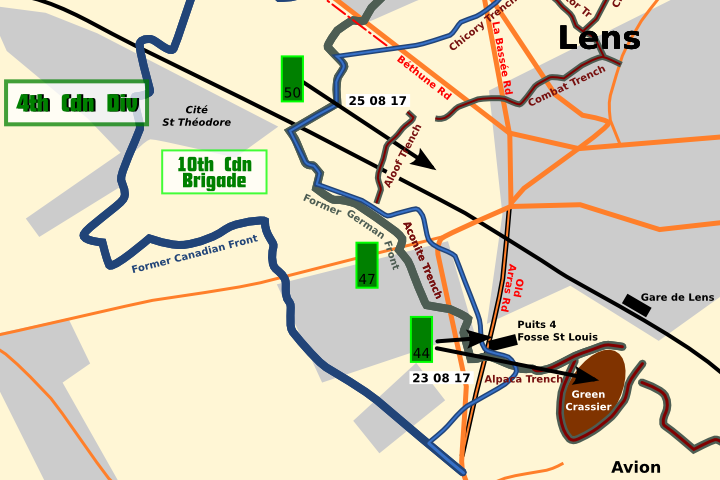

The failure of the 50th Battalion to take Aloof Trench in the engagement on the 21st August 1917 meant that the Germans retained a small salient in the area (A salient is where your line bulges into that of the enemy).

On the evening of the 22nd August Currie met with Major General David Watson (4th Division) and Brigadier General Edward Hilliam (10th Brigade).

Hilliam put forward the proposal that his Brigade would capture a position known as the Green Crassier (because of the vegetation growing on the slag). Taking this objective would complete the encirclement of Lens.

The crassier still exists and it is still green. It forms part of the Parc de la Glissoir in Avion.

Hilliam’s idea was to use a single Battalion (The 44th; from Manitoba) to drive a corridor through the German lines and capture the hill. This act it was hoped would cause the Germans to evacuate Lens. The three Canadian Generals seem to have been so mesmerized by the prospect of taking Lens that none of them appears to have considered what would happen to the 44th Battalion if the Germans remained as obstinate as they had after being assaulted by two Divisions.

As the Canadian Official History describes it:

It was to be a costly and unprofitable task.

The attacking route required the Canadians to pass immediately to the right of the Fosse St Louis; one of the local pit heads. It was believed that the pit buildings had been cleared of Germans: the path towards the crassier could be quickly secured. This was essential if the small party sent forward was to be supplied with sufficient material to fortify the crassier.

The confusion over Fosse St Louis

In fact the mine was extremely well held by a battalion of the 64th Reserve Infantry Regiment. In addition to the garrison strength the Germans had use of tunnels through which they could bring up reserves.

In a report to 10th Brigade (dated the 26th August 1917), the 47th Battalion stated that they had mopped up Fosse 4 on the 22nd August but only because of the proximity of its location to their new position. The report goes on to explain that evidently there was some confusion between Fosse 4 and Fosse St Louis. The latter being an extremely well held building with tunnels that would accommodate up to two battalions.

On the trench maps the complex is marked Puits 4, Fosse St Louis. Regardless of what Major Mills of the 47th Battalion might have thought, looking at the ruined buildings in front of him, the two names refer to the same mine. Fosse 4 (that is the entire colliery complex) was named St Louis. Unusually it only had the one pit (Puits) No 4. Unfortunately the Canadians were mixing their terminology. When 10th Brigade ordered the 47th Battalion to put a post in Fosse 4 they did; but apparently only in one of the buildings.

44th Battalion

As the men of the 44th Battalion gathered in their jumping off positions at 0100 hours a patrol brought in the news that they had found that the Fosse was held in depth. Lt Colonel Reginald Davies, commanding the Battalion, was forced, at short notice, to split his force. One company (In some reports it is named as D in others No 4) would be sent against the Green Crassier whilst two platoons would neutralise the mine buildings. As one of his four Companies was on loan to the 46th Battalion this left six platoons to mop-up and ensure the free flow of equipment forward. Zero hour was at 0300 hours on 23rd August 1917.

Advancing from the Arras Road behind their barrage No 4 Company made steady progress towards the crassier and within thirty minutes they had climbed its sides and secured themselves on its summit. There was no trench; no defences; just abandoned coal trucks and debris.

Below and behind them the two platoons designated to take the mine were held at bay for over five hours by continual machine gun fire. At 0830 hours the Canadians finally managed to get into the Fosse buildings. The fighting though, was from finished as the Germans mounted counter attacks throughout the day. The buildings changed hands numerous times, echoing the fighting at Verdun or in a later war; Stalingrad. Having control of the tunnels meant that if necessary the Germans could simply withdraw to safety; then have their own artillery shell the Canadians and attack again. They eventually succeeded in throwing the Canadians out definitively.

The supporting troops from No 1 Company (A Coy) seized Alpaca Trench but this did not extend quite as far as the crassier and with the intervening ground coming under constant fire it was impossible for those on top of the crassier to either retreat or receive desperately needed munitions and support.

Colonel Davies’ report states how :

There was only a narrow shelf up the face of the cliff. This was swept by heavy machine gun fire.

Every man who tried to get up or down was hit and absolutely no one came back from the top of

the crassier after daylight.

During the day the Germans repeatedly attacked the crassier from all sides. A forlorn and heroic stand was made by the survivors as they scraped holes into the coal slack but with limited ammunition and grenades with which to defend themselves the end was inevitable. By the afternoon of the 24th August the crassier was back in German hands.

Sounds of fighting were heard on the crassier until 3.00 in the afternoon, when

the enemy was seen to be in full possession.

In this misguided assault the 44th Battalion lost 23 killed (the CWGC have 41 casualties for the day), 115 wounded and 118 men missing (including 70 taken prisoner on the crassier and a further 17 at Fosse St Louis). As Colonel Davies points out himself the assault had been conceived with the impression that Fosse St Louis was empty. It was only his own uncertainty that had led him to send out a reconnaissance patrol. Without that premonition the attacking platoons would have been swept by the flanking fire of the Fosse’s five machine guns.

Both positions remained in German hands until they gave them up in the great retreat at the end of the war.