Armistice

The Cenotaph

In order to commemorate the signing of the Peace Treaty at Versailles on the 28th June 1919 it was decided that a victory parade should at some stage be held in London.

It should be remembered that the 11th November 1918 was an armistice (cessation of operations)

not an end to the war.

The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George later attended the Parisian celebration on the 14th July and was greatly impressed by the French soldiers marching past a catafalque placed near the Arc de Triomphe. It represented all those who had died and each column of soldiers saluted in honour as they passed.

Lloyd George envisaged something similar and the task of designing a monument was given to Sir Edwin Lutyens (responsible for the Thiepval Memorial and many of our cemeteries).

Like the French monument it was not intended that any design would be permanent and Lutyens was asked to design a non-denominational shrine, made out of wood and plaster.

It was Lutyens who suggested this structure be named The Cenotaph which is derived from Greek words meaning: empty tomb.

It had been important in ancient Greece to carry out a proper burial for their fallen — even when it had not been possible, for whatever reason, to recover the body. A cenotaph therefore represented the fallen hero himself.

The Cenotaph was unveiled on the morning of the 19th July 1919 and the parade took place in the afternoon — led by the Allied and American commanders in chief. (America had never been an Allied nation.)

In theory the Cenotaph was intended to act as a point of reference during the parade and it was never thought that it would touch the public in the way that it did.

Within days however flowers were piling up around the temporary structure’s base and many in power began to move that a permanent memorial should be created in stone.

Consideration was given to moving the site to an emplacement where traffic would not be bothered, but finally it was accepted that its position in Whitehall had become engraved on the national consciousness. It had been there that the generals had saluted the dead.

Lutyens submitted his final designs and these were approved for an unveiling on the 11th November 1920. His design is remarkably simple at first sight and it often takes a second glance to realise that it represents a tomb surmounted on a stepped pylon.

There is little in the way of decoration apart from the dates of the two world wars, two wreaths on the sides and one on the tomb. On the sides can be read: The Glorious Dead.

Lutyens died in 1944 but left behind him a request that should the Cenotaph become the national memorial at the conclusion of the current war that only the dates should be added and this was done on the two sides parallel to the pavement.

The design looks so simple and yet that is so far from the truth. There is not a single straight horizontal or vertical line — everything is curved. If you could extend the sides upwards you would find that they would meet a thousand feet above your head (305 metres).

There are six flags (three facing each pavement) surrounding the Cenotaph. On one side the Union Flag with the Red Ensign and the RAF Ensign whilst on the other the Union Flag is flanked by the White Ensign and the Blue Ensign.

As a memorial to all of the fallen it deliberately leaves out any form of religious symbols.

The Unknown Warrior

As the plans were arranged for the unveiling of the Cenotaph by King George V on 11th November 1920, a proposal was also put forward that the body of an unknown soldier should be honoured at the same time.

The instigator of the proposal was an ex-military padre: the vicar of Margate, the Reverend David Railton MC.

One night having just led a funeral near Erquinghem in the Pas de Calais he returned to his billet where a single grave had been dug in the garden. A wooden cross had been raised above the grave stating quite simply that it belonged to an unknown British Soldier of the Black Watch.

The memory stuck in Railton’s mind and in August 1920 he wrote to the Dean of Westminster Abbey, Doctor Herbert Ryle, suggesting the idea of bringing home one such unknown soldier to represent those who had died and in particular, all those who had no known grave. It would give the nation a point of focus for honouring the dead.

Doctor Ryle was enthusiastic about the idea and suggested it to the King who thought that the proposal was far from sound especially so long after the war.

Not to be put off by mere royal dissent Ryle contacted the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George who was equally enthusiastic and used his Welsh wiles to talk His Majesty round.

A committee was set up and it was agreed that the final resting place of the soldier would be Westminster Abbey.

Orders were sent out to France and Belgium for the recovery of a British Empire serviceman who could not be identified from each of the main battlefields: the Aisne, Arras, the Somme and Ypres. (Some mention six bodies but the only confirmed accounts state four).

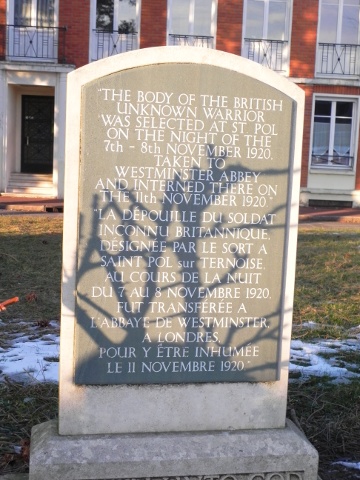

On the 7th November 1920 the four soldiers were brought to the Military Chapel in St Pol sur Ternoise in the Pas de Calais where, following the end of the war, the British Army had set up its Headquarters.

They were placed on stretchers and each was covered by a Union Flag. The delivering parties were immediately ordered back to their units to ensure that nobody would know that their man had been the one chosen.

Originally though to have taken place the same day, Brigadier General L J Wyatt (Commanding the forces in France and Belgium) records that it was the night of the 8th/9th that he entered the chapel. The solemnity of the moment cannot have escaped him and after reflection he placed his hand on one of the bodies.

This one was placed in a simple coffin whilst the other three were removed for re-burial.

The CWGC have no idea where these three graves are located. There are two Great War military plots in St Pol and neither appears to contain post 1920 unidentified burials. Major General Sir Cecil Smith stated that they were buried beside the Albert-Bapaume road to be discovered there by parties searching for bodies in the area.

In the afternoon the coffin was transferred to the Château at Boulogne sur Mer where it was placed in the library; transformed for the occasion into a chapel. There it spent its last night on Continental soil surrounded by a Guard of Honour formed by Poilus from the 8e Régiment d’Infanterie (The St Omer Regiment).

Early on the 10th the coffin was placed in an oak coffin, recently arrived from England. It had been fashioned from a tree from the Royal Palace at Hampton Court and was bound in iron bands. A crusader-style sword presented by the King from his own collection was passed through one of them. The lid bears the words: A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country.

Whilst in common parlance we generally say Unknown Soldier the correct term is Warrior as there was always the possibility that the unidentified remains were those of either an airman or a sailor (The Royal Naval Division fought on land). The body could also have come from any of the nations within the Empire.

The coffin was draped in the flag that David Railton had used as an altar cloth during the war. It is known as the Padre’s Flag and now hangs in St George’s Chapel, Ieper.

Drawn on a French gun-carriage and accompanied by soldiers from the 8e and 39e RI (From Rouen), 6e Chasseurs à Cheval (Light cavalry) and Fusiliers Marins of the French Navy the coffin was brought to the Quai Chanzy in the harbour. In front, soldiers carried wreaths from the townspeople, French government and their defence forces as well as those British formations still in France.

A huge crowd was present and many of the shops closed their shutters as a mark of respect.

At the quayside Maréchal Ferdinand Foch the former Commander in Chief of the Western Front paid tribute to the Empire’s fallen.

Lieutenant General Sir George Macdonagh replied on behalf of the King telling the French people that:

We are taking the body of this simple soldier to lay him in Westminster Abbey, the most sacred of all places in Britain, where lie our heroes and Kings. His tomb will remain for centuries as a souvenir of the friendship, sympathy and love that unites and will forever unite Britain and France.

The coffin is carried aboard HMS Verdun

At 1130 hours the coffin was carried aboard the destroyer HMS Verdun by British servicemen. She had been specially chosen as her name would pay homage to the tens of thousands of Frenchmen who had died during that terrible battle.

As HMS Verdun set sail for home she was escorted by five French warships until reaching British waters where the Royal Navy took up the escort.

As she pulled out of the harbour a Field Marshal’s nineteen gun salute marked the unknown soldier’s departure from France and was echoed by the guns of Dover Castle on reaching the coast.

As the coffin was brought ashore it passed a Guard of Honour formed by the 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers as it was taken up to the Marine Railway Station for the journey to Victoria Station in London.

In a parallel version of events, the French were also in the process of honouring an unknown soldier (theirs was definitely a soldier — and French).

11th November 1920

And so on the morning of the 11th November 1920 the Unknown Warrior, borne on a gun-carriage drawn by six black horses, approached the Cenotaph. The horses were from the only team that had survived the war intact. The dozen accompanying pallbearers included Field Marshals Lord Haig and Lord French, Admiral Lord Beattie and Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard

At 1100 hours, two years to the moment since the Armistice, Big Ben struck the hour and King George V unveiled the Cenotaph. The assembled crowd bowed their heads in silent reflection for two minutes and the sounds of the Last Post rang out.

The cortège then continued on its way down Whitehall past Downing Street to Westminster Abbey. There a hundred soldiers lined the nave — each of them a holder of the Victoria Cross and under the command of Lt Colonel Freyburg VC.

The congregation was led by the Royal Family but the majority of those there were mothers and widows who had lost their husbands and sons. The burial service was short and simple and the coffin was laid to rest in a tomb at the west end of the nave.

A hundred sandbags of soil from the French battlefields were used to fill in the tomb.

Immediately after the funeral thousands began to file past the Cenotaph, laying a carpet of flowers and wreaths. An estimated 40,000 visited the Abbey before the doors were finally closed, an hour late, at 2300 hours.

But the crowds stayed on throughout the night adding to the ever growing mound of flowers at the Cenotaph. A sea of people slowly filing along Whitehall from Trafalgar Square and far from just being local Londoners they had come from all over the British Isles.

As the new working week commenced on the 15th the pilgrimage continued. Buses slowed as they passed the Cenotaph and their passengers stood in respect. And on they came. The grave of the Unknown Warrior was closed on the 18th November by which time Abbey officials estimated that well over a million visitors had passed through their doors.

On a pillar near to the grave hangs the Congressional Medal of Honor which General Pershing had conferred on behalf of the American Nation on the 17th October 1921. You can also see the bell from HMS Verdun.

A slab of black Belgian marble from Namur which was unveiled at a ceremony on Armistice day 1921 seals the tomb and its inscription composed by the Dean gives details of the interment.

The inscription finishes with the words:

They buried him among the Kings because he had done good toward God and toward his house.