The Crows Nest

The Crow’s Nest

The Crow’s Nest is a large hillock rising about 10 metres above most of the surrounding countryside. From its summit the German machine gunners had a splendid view of all before them as well as a dominating position overlooking Hendecourt itself.

| GPS | N | E | OSM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decimal | 50.21891 | 2.95480 | Map |

The position was important because it sat immediately in front of the Drocourt-Quéant Switch which was the next sector of the Hindenburg defence system that had to be overcome.

Whilst not a major battle the Crow’s Nest was an engagement carried out solely by the 15th Bn Canadian Infantry (48th Highlanders of Canada). Today the Crow’s Nest (known locally simply as: le mont – the hill) remains much as it was, uncultivated, bristling with trees and although hollowed out in places by post war quarrying, the ground lends the idea of a shell battered and fought over emplacement. And the shells are still being found to prove it.

View from the location of Ulster Trench

Crow’s Nest on the left and Hendecourt village on the right

Zero hour

Zero hour was set for 0450 hours on the 1st September. It would still be dark but that would be to the advantage of the Canadians.

At 0100 hours the four companies moved forward to make contact with their guides at the end of Unicorn Avenue. From there they were brought up to the jumping off positions.

No 2 Company under Captain Andrew Samuel (139 men) moved forward to the (accurately named but lacking in subtlety) Cemetery Avenue whilst Captain Gordon Winnifrith and No 4 Company (135 men) formed up on their right along the Hendecourt Road. Behind them and remaining in Unicorn Avenue, No 3 Company commanded by Lt Thomas Cowan (126 men) were in support and No 1 Company were in reserve – Captain Hugh Edge and 138 men.

Another factor that needs to be raised is that at this stage of the war, commanders on the ground were often given little time for intelligence gathering or reconnoitring the lay of the land. This was not going to be a set piece Show where the enemy’s composition; strength and deployment had been the subject of much research and the operation weeks in the planning.

Looking back towards Upton Wood from the Crow’s Nest

Upton Wood Cemetery is on the right edge of the wood

The Highlanders had little idea as to what the Crow’s Nest actually contained or how well defended it would be. They were to be given a barrage that lifted 100 metres every 4 minutes and with little in the way of information about the state of the German defences it was decided to rush the hill in the one go.

At 0450 hours the Canadian guns opened up and the leading companies leapt to their task.

All went well and the casualties were light as the men slithered their way across the battle churned fields to their objectives. As soon as the barrage moved off the crest of the Crow’s Nest, Captain Samuel’s No 2 Company stormed up the slope and took the German machine gunners before they had been given the slightest chance of setting up their guns.

His men then continued their advance to the far side of the hill allowing No 3 Company to complete the mopping up operation.

A general map of the battle zone

The approximate location of trenches mentioned in the narrative are given

The owners of the Crow’s Nest explain its local history

On the right the men of No 4 Company rushed the wood around the château quickly taking a number of machine gun posts.

Visitors today should realise that the château was badly damaged by Australian artillery during the Battles of Bullecourt in 1917. It was rebuilt after the war, in a different style.

To slightly complicate matters the right of the Canadians was also the limit of First Army. The attack against Hendecourt village was going to be carried out by the British 57th Division of Third Army. The 8th Bn King’s (Liverpool) Regiment set out at the same time as the Canadians but encountered considerable resistance in front of Hendecourt.

As Captain Winnifrith’s men tried to consolidate their position they came under sniper fire from their exposed right flank. Fortunately No 1 Company (in reserve) sent up a couple of platoons who formed a defensive flank facing the village. It was whilst moving forward that Lt Brian Loudon known as The Laird was killed by shell fire. He is buried nearby at Dominion Cemetery where you will also find other casualties from the day’s fighting.

By 0600 hours, messages were being flashed back: Crow’s Nest taken, 50 prisoners, 1 Officer. Casualties light.

Half an hour later the 8th King’s broke into Hendecourt and to the north of the Crow’s Nest No 3 Company along with soldiers of the 14th Bn CEF (Royal Montreal Regiment) had taken Hans Trench.

The château today

Behind the château runs a sunken road towards Cagnicourt and running off this was Trigger Alley which still appeared to be well defended by the Germans.

By 0830 hours the new front line had taken form with two companies of the 2/7th King’s now holding Greyhound Avenue (the southern continuation of Trigger Alley), No 4 Company were in the château grounds and No 2 Company were slightly beyond the Crow’s Nest. The two Canadian companies however had not been able to properly link up due to the constant machine gun fire coming from Trigger Alley.

Perhaps the most exciting event of the morning occurred at 1100 hours when Private Marshal, a Lewis gunner from No 2 Company managed to shoot down a German two-seater aircraft that had strayed over the lines.

Brigadier General Young presents M Bruno Marquaille

with a Regimental gift in appreciation of his being allowed to visit the site

For their part the Germans spent the remainder of the day trying to bomb (that means: grenade) their way back down Hans Trench and about 1730 hours it was becoming evident to the Highlanders that German reinforcements were gathering along the Drocourt-Quéant line ready for a counter attack.

The attack came at 1810 hours, once again along the Canadians left flank, down Hans Trench. As the preparations had been well observed the Canadian artillery were already primed and stopped the advance within 20 minutes.

It has to be said that throughout the day the Highlanders had been subjected to a lot of their own artillery shells falling short.

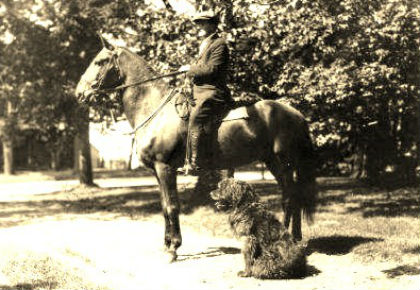

Lt Colonel Charles Bent on his farm with Fritz the horse

and the battalion mascot Bruno the dog

The day’s success was crowned by the arrival during the night of a German officer on horseback. He had been away on leave and had no idea that the Crow’s Nest had fallen. The officer was taken prisoner by Captain Winnifrith and his rather fine horse confiscated. When Lt Colonel Charles Bent returned to duty as Commanding Officer of the Highlanders he took the horse as his own and renamed him Fritz. Both horse and new master would reach Canada at the end of the war.

The day belonged to the Highlanders and they could perhaps now claim that it had indeed been a one horse show.