Chemin des Dames 1917

Sapigneul : April/May 1917

Courage and Mutiny

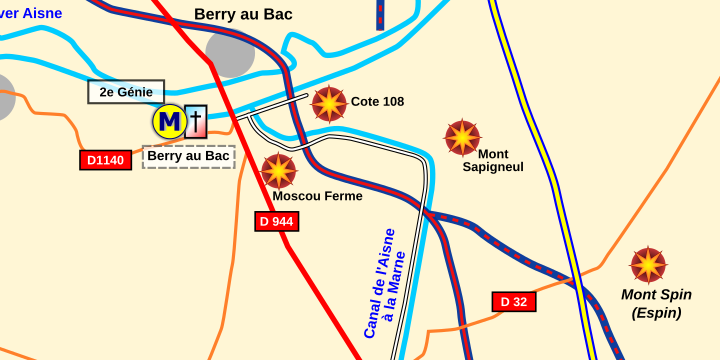

A short side trip down to the village of Berry-au-Bac brings out a couple of events relating to my own village.

Coming into Berry-au-Bac from the north you cross first the Aisne and then the canal. The canal branches to the south at the road bridge, and then arcs away from the road for about a kilometre before coming alongside again near the Maison Bleue (Cormicy) French Military Cemetery.

| GPS | N | E | OSM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decimal | 49.39805 | 3.90202 | Map |

The Aisne with Cote 108 behind it

Just behind this canal T-junction is a small hill, known as Cote 108, and behind that again a dense forest of trees on another hill called Sapigneul.

Further down the road and looking away from the Maison Bleue Cemetery, towards the canal, you can see another hill with the A26 autoroute running across it. This was known as Mont Spin in 1917 but is now marked on maps as Mont Espin.

These three hills were assaulted at enormous cost by the French and in the end provoked one of the first serious mutinies of the campaign.

The front in April 1917 was basically divided between the 40e Division d’Infanterie (XXIII Corps) on the left and 37e DI (VII Corps) on the right.

As part of the 37e DI, the 3e Régiment de Zouaves were already in the trenches in front of La Neuville (The crossroads near the cemetery) on the 4th April. The diary remarks that it either snowed or rained every day. The trenches churned by shelling and the constant rain were little more than streams of liquid mud.

Then on the 4th after a sudden bombardment the Germans launched an attack on the French lines. For a moment the Zouaves were almost surrounded as the flanking regiments gave way, but after a savage hand to hand fight in the trenches the French threw the Germans out and forced them back to their own lines.

Initially disappointed the Germans soon discovered that they had struck gold. They had managed to capture one of the Zouave’s Sergent-Majors who had the entire set of plans on him for Nivelle’s Offensive in this sector.

The forested hill of Sapigneul

The Nivelle Offensive

On 16th April 1917 the 40e DI rushed forward and secured Cote 108 and Sapigneul but the German machine guns on Mont Spin to their right had not been silenced by either the bombardment or the 37e DI assault, and were soon tearing holes in the flanks of the 40e DI.

The Division was forced to give up what gains it had made on Sapigneul at terrible cost to the regiments.

On the right the 37e DI met much the same fate attacking Mont Spin. The 3e Zouaves together with the other regiments in the front line surged out of their trenches at 0600 hours.

The night had been cold and wet but the men were in fine form, it was just like the first day of the Somme. The men were certain of victory, their generals had assured them that the enemy had all been massacred by the artillery.

The Zouaves diary actually says that the departure from their own trenches was as though on manoeuvres it was so ordered. Then just like the Somme the soldiers’ enthusiasm and belief in certain victory was crushed within the first fifty metres.

The German machine guns open up, cutting swathes through the neat ranks and then their artillery puts down its counter bombardment. Dashing from point to point the remnants reach the German barbed wire – which is still intact.

The German defenders seemed to be everywhere at once (like the Chemin des Dames ridge there are numerous tunnels and quarries) and the French find themselves being shot at from behind as well.

As the diary says: even the bravest found themselves helpless against such odds.

The Russians enter the fray

At 1100 hours following a second bombardment, the two divisions renewed their assaults but they met the same fate as the first. During the evening and under the cover of darkness the French manage to crawl back to the safety of their own lines.

Despite Neville’s promise to call it all off in the case of failure after 48 hours, the next few days around the three hills are like Verdun.

One side would attack and take a few hundred metres of trench. The defenders would rally and put them back out of it again. Neither side could gain the upper hand.

The 3rd Russian Brigade were brought up to attack Mont Spin and although they too had some success, the machine guns took their toll and the Russians were forced back down the hill to their own trenches. Their dead can be found in the French cemeteries nearby.

On the 20th both Divisions had to be, not only rested, but withdrawn from the front. Both had lost about half of their effective strengths in the four days of hard fighting.

The arrival of the 4e and 3e Divisions d’Infanterie

Following a forced march of thirty-eight kilometres the 4e DI arrived on the front on the 21st and took over the left sector, in front of Sapigneul the next day. To reach the front the soldiers had to clamber over makeshift wooden bridges strung across the canal, which were under the eyes of the enemy observers higher up the slopes.

Within days, some soldiers reckoned it was safer staying in the trenches than risking the return to get fed.

In front of Mont Spin the 3e DI settled in.

Both Divisions were made up of Picards and Ch’ti (Northerners in their own tongue) and thus provided the regiments for many of the men from my village.

| 4e Division d’Infanterie | 3e Division d’Infanterie |

|---|---|

| 120e Régiment d’Infanterie (Peronne) | 51e RI (Beauvais) |

| 147e RI (Sedan) | 87e RI (St Quentin) |

| 328e RI (Abbeville — Reserve) | 128e RI (Abbeville) |

| 9e Bn Chasseurs à Pieds (Longuy) | 272e RI (Amiens — Reserve) |

| 18e BCP (Longuyon) |

Each Active Regiment had a Reserve: Numbered 200 plus the regimental number: 128e and 328e. In general the Active was composed of battalions 1-3 and the Reserve 4 and 5. The chasseurs, however, were made up of single battalions.

The Second Offensive

On 4th May Général Nivelle ordered a second offensive along the Chemin des Dames — and for the Fifth Army on the right flank this meant taking the elusive hills of Sapigneul and Spin.

The French bombardment was pathetic, with the field artillery making up the most of it, for by now, the heaviest guns were down to just fourteen rounds apiece.

The 3e DI attempted to take Mont Spin on the 4th, 7th and again on the 9th. A little territory was gained but the enemy’s ability to use tunnels and pop up here and there created havoc.

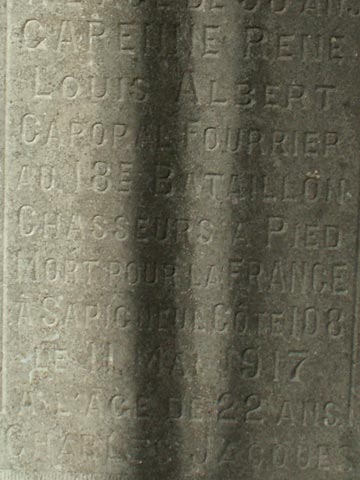

In front of Sapigneul the 18e Bataillon de Chasseurs à Pied (BCP) went forward once more on the 11th but were so crippled by losses that within ninety minutes of leaving their trenches the straggling remains of the battalion were back in them again.

One of those left behind is Caporal René Gapenne, 22 years old and from my village.

The following day the Battalion was withdrawn and not long afterwards everything they had struggled to gain was forcibly retaken by the Germans.

It became quite apparent that all was not well within either Division. German intelligence carries an announcement that the 18e BCP were refusing to march and that their Divisional Artillery had put up a sign saying that they refused to fire.

Enough of this — we won’t go !

On 14th May the 128e Regiment d’Infanterie (from Abbeville) were relieved from the line and marched back to Prouilly (a few kilometres to the south west) for what they believed to be a long earned rest after a week’s bloody fighting.

They soon discover that this was not to be the case when on the 20th they were ordered back to the front again.

The cry goes up: On ne montera pas — we won’t go.

The soldiers were fed up with their lifestyle in the trenches. Poor food, lack of amenities and one of their biggest complaints : the lack of Permissions (Leave of Absences). The men were not getting their due time off with their families.

One of the men : Soldat Paul Breton, a school teacher in civilian life, took the matter further. It is time for peace, enough of these ill prepared and bloody offensives that are a waste of men’s lives, he told a gathering of some 400 protesters.

The Commanding Officer, Lt Colonel Nouvion arrived on the scene to try to talk sense into his men but without success. Then the Divisional Commander: Général Cadourdal arrived with machine guns instead of words.

One of the Companies was talked into heading back up to the line and slowly but surely the rest started to follow but Breton and other declared ring leaders were arrested.

A Military Tribunal sentenced Breton and the other leaders to death, but Breton was a wily soldier and managed to get a letter out to influential people.

The French government fearing further grave incidents of disobedience decided to commute the sentences.

Lt Colonel Nouvion found himself relieved of his command and General Cadourdal was posted. As for the Regiment, they were transferred to Bar le Duc on the Verdun Front, 180 kilometres away. They were told to undertake the journey on foot.

When leave was properly reinstated, it was found in some Divisions that they were having to let up to half their strength away at any one time in order to catch up with the backlog that was owed to the men.

There were few cases of actual violence against officers during any of the mutinies along the front, and the Germans found that the will to defend the line against German attacks was as strong as ever. The Poilus wanted peace — but on French terms.

A little further down the road near the Fort de Brimont a number of regiments took part in demonstrations against the war and French troops opened fire on some of the agitators.

On the opposite side of the main road and sign posted from the village of Berry au Bac you will find the local French Military Cemetery which contains nearly 4,000 of those who fell in and around this area. It contains a CWGC plot containing a number of members of the 12/13th Northumberland Fusiliers who were defending this section of the canal in May 1918 as the Germans launched their Blücher Offensive ; the same offensive which wiped out the 2nd Bn Devonshire Regiment.

A short drive up the main road will take you to the Berry-au-Bac Tank Memorial.